The story’s third version has it that the two men Print sent to bury the bodies started a bonfire to thaw the frozen bodies, making them easier to bury, and inadvertently set the bodies on fire. For pure color, I prefer version number two, but the truth will always be elusive.

Absent the conflagration, the hanging of Ketchum and Mitchell might have slipped into obscurity as the hanging of two rustlers, not an uncommon occurrence in cow county in those days. But a spark from the cigarette of a drunk hotelkeeper in a remote draw in southern Custer County changed everything.

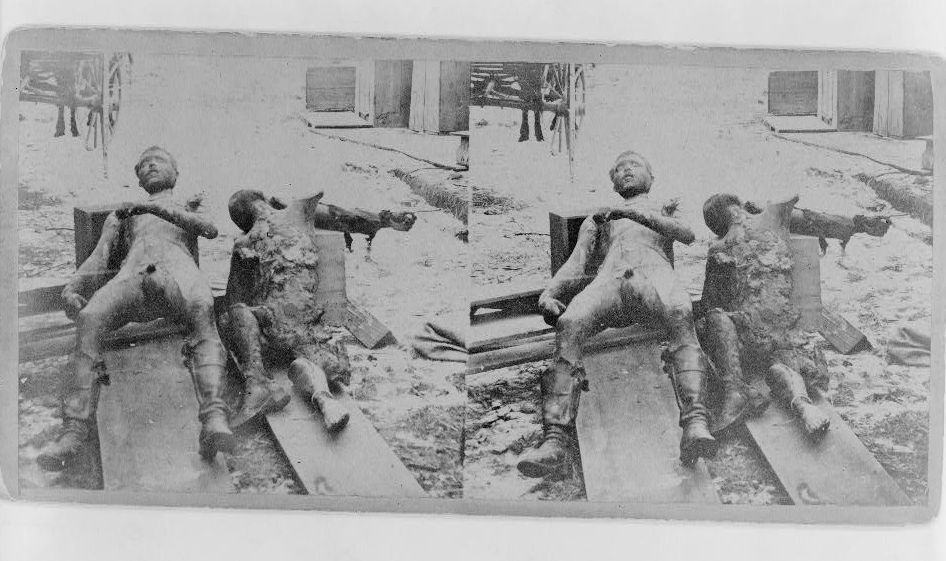

The bodies of Ketchum and Mitchell were taken by train to an undertaker’s establishment in Kearney. Before the undertaker had a chance to embalm the bodies, a Kearney photographer. H. M. Hatch, took the photograph below. He printed it and sold hundreds of copies. One of the copies fell into the hands of the editor of the Nebraska State Journal, and from there it spread like wildfire to both coasts.

That single photograph changed the fortunes of Print Olive and his dream of a cattle empire extending from the South Loup of Nebraska to the Yegua brush country of Texas. Instead of Olive family mansions surrounded by thousands of acres of Sandhills grasses, and executive boxes at Memorial Field in Lincoln, filled with cowboy hat-wearing, Husker-cheering fourth generation descendants of Print, there’s a lonely, untended grave in the Maple Grove Cemetery in Dodge City, Kansas. Searching through phone books of communities in central Nebraska, one finds no mention of an Olive. Instead of his reputation as a respected cattleman, the term ‘man-burner’ was spit out in endless western saloons.

The vengeance ended in carnage and we thought the photo ought to stick in our memories. Steve had a strong feeling that the kinds of behaviors and attitudes that produced that carnage would always produce carnage, anywhere and everywhere, if it were to be unleashed. But the photo and the carnage are not the end of that photo’s story. We go on here to see how dramatically a single photo can change the course of things.

That same photo played an over-sized part in changing the momentum of the county’s westward expansion. Print’s view that this newly opened country was a means to building a cattle empire was replaced by the belief that cattle raising was one way to build a new country. Print’s view that the six-shooter was the tool of order was replaced by laws enacted by the citizens of this new country. So, if it can be said that the Confederacy won the battle of Devil’s Gap, it was now true that the Union’s insistence on a country of laws was to prevail. Print couldn’t have given the Unionists and law and order believers a greater gift than the unintended result of a spark in Devil’s Gap.

Here’s what happened in the ensuing weeks. As word of the murders and their brutality spread east, two men emerged, determined to bring the Olive gang to justice, and to establish the rule of law in the entire state. In the November elections, General Sherman’s former brigadier general, Caleb Dilworth, a lawyer-cattleman from Plum Creek, had been elected the state’s Attorney General. He had previously served as the prosecuting attorney in Nebraska’s Fifth Judicial District over which Judge William Gaslin presided. Recognizing that it would require the full power of the state to bring the cattle kings to justice, he met with outgoing Governor Silas Garber.

Garber agreed. “The time has come to start enforcing the laws of the state all the way up the Platte to the Wyoming Territory. Our state has only one set of laws, and they apply to every citizen—settlers, cattlemen and townsfolk.” He pledged his and the state’s full support.

Dilworth, a general in every sense, devised a plan with the same precision he had exhibited as commander of the Army of the Cumberland’s XIV Corps. Twelve deputies were recruited-Ami Ketchum’s two brothers, Samuel and Lawrence, and ten Kearney townsmen from the old Kearney Guard, a troop that had been organized six years before to protect settlers from gun-happy Texas cowboys who had come up the trail with herds of longhorns. They were assembled in Kearney, instructed in the roles that each would carry out, and on the night before the arrests were to take place, secreted into Plum Creek via train. Each was met on the outskirts of town and driven to their marshalling point. Surprise was the key element of Dillworth’s strategy.

The General enjoyed one big advantage. Print Olive was supremely overconfident. He never imagined anyone could threaten him in his stronghold of Plum Creek. He freely strolled the streets, drank in the saloon, played cards at the hotel table, secure in the belief of his invincibility. Olive smirked at the sensational accounts of the murder blazoning the pages of the Central Nebraska Press, the Eaton family newspaper in Kearney.

“Gravestones cry out against you. Hell longs for you. The cries of these dying men will ring in your ears forever and through endless eternity. You will hang in burning chains over fires even as you hung these two innocent mortals.”

“Mighty big words from some suit-wearing pilgrims,” Print scoffed. “How many guns does the Kearney press control on the South Loup?”

Turns out the answer was, enough. Olive and his five indicted codefendants were picked off, one by one, that very Sunday morning as they walked the quiet streets of Plum Creek. Not a shot was fired, and the cowmen were whisked off to Kearney on a waiting train, and then, for safer keeping to the state penitentiary in Lincoln.

Radical Winds ~ by Steve Buttress, posted by Chuck Peek