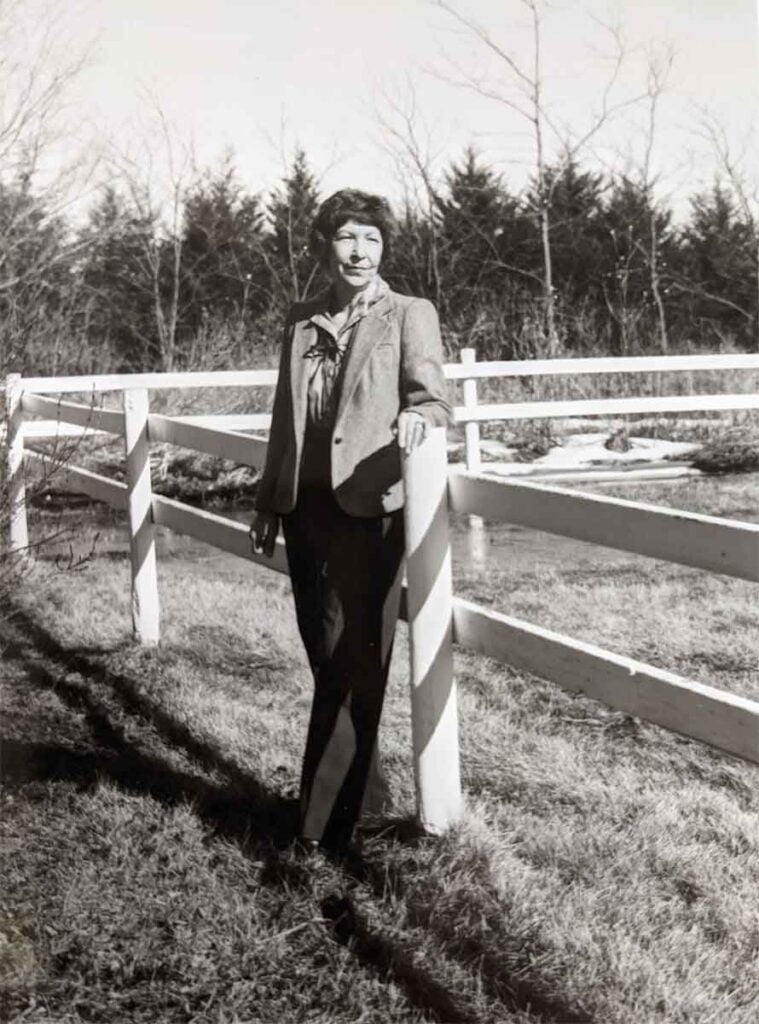

Poet. Farm woman. Professor. Disabled. All words Shirley Buettner (1934-2008) used to describe facets of her identity. Born in Kansas in 1934, Buettner relocated to Nebraska with her family in 1945. She completed a BA from Kearney State College (KSC) in 1956. She taught high school for several years, raised 3 children, and did the bookkeeping for a family business, before launching her literary career in the late 1970s. Buettner was already a published poet when she returned to KSC to study with fellow Nebraska poet Don Welch. Buettner received her MA in 1984 with a creative thesis in original poetry entitled “Only the Doe Remains Voiceless.”

Buettner published widely in the 1980s and 1990s, mostly in small regional and local journals like ‘Platte Valley Review, “ ”Kansas Voices,” and “Prairie Schooner.” “Her poems were also anthologized regularly. “Hurdles,” published in “All My Grandmothers Could Sing,” was even adapted into a modern dance by the University of Nebraska Omaha. In addition to publishing in a wide array of magazines, small press publications, and anthologies, Buettner also authored two chapbooks, both published by Juniper Press (La Crosse, WI). Her first book, “Walking Out the Dark,” was published in 1984 with “Thorns” following in 1995. Prominent Nebraska poets described her work as “strong medicine for the heart,” full of “tough lyricism.”

Buettner was part of a flourishing poetry community. She regularly worked with well-known Nebraska poets, including Don Welch, Ted Kooser, Bill Kloefkorn and more. She taught at writing camps, conferences, and workshops, taking joy in mentoring budding poets. Despite suffering a major stroke in 1991, Buettner remained active in the local poetry community, organizing monthly “Poetry with Shirley” sessions in which she highlighted Great Plains poetry for her assisted living facility.

Buettner was a meticulous record keeper; she donated several boxes of draft poems, correspondence, and other materials to the University of Nebraska at Kearney (UNK) Archives and Special Collections. This material allows one to track the development of specific poems as well as broader scale changes in Buettner’s style. Her correspondence shows the process of getting published (including weathering many rejections before any particular poem made it to press). It also hints at the challenges faced by small publications as it wasn’t uncommon for Buettner to receive a rejection because a press was closing or going on hiatus.

Buettner’s poems speak to the beauty of the Plains.

“Discovered”

While clearing the west

quarter for more cropland,

the Cat quarried

a porcelain doorknob

oystered in earth,

grained and crazed

like an historic egg,

with a screwless stem of

rusted and pitted iron.

I turn its cold white roundness

with my palm and

open the oak door

fitted with oval glass,

fretted with wood ivy,

and call my frontier neighbor.

Her voice comes distant but

clear, scolding children

in overalls

and high button shoes.

A bucket of fresh eggs and

a clutch of rhubarb rest

on her daisied oil-cloth.

She knew I would knock someday,

wanting in.

“The Wind Chimes”

Two wind chimes,

one brass and prone to anger,

one with the throat of an angel,

swing from my porch eave,

sing with the storm.

Last year I lived five months

under that shrill choir,

boxing your house, crowding books

into crates, from some pages

your own voice crying.

Some days the chimes raged.

Some days they hung still.

They fretted when I dug up

the lily I gave you in April,

blooming, strangely, in fall.

Together, they scolded me

when I counted pennies you left

in each can, cup, and drawer,

when I rechecked the closets

for remnants of you.

The last day, the house empty,

resonant with space, the two chimes

had nothing to toll for.

I walked out, took them down,

carried our mute spirits home.