John Raimondi’s career as a sculptor began with the models he built in the apartment in which he lived above the hobby shop where model kits were plentiful. He was in the Boston area then, you can tell that Boston remains with him when you hear his voice.

Those model kits evolved into adventures in building hot rods and learning from that the essentials of sculpture, which evolved again in his first years attending art schools, into his fascination with the possibilities of monumental sculpture.

His commission from the Bicentennial Project was only his second commission, and the controversies over his entry “Erma’s Desire” (for the Grand Island, Nebraska I-80 highway rest stop) gained him his first splash in the national news. All for his sharp depiction of his mother’s investment in the happiness of her children, John and his three brothers. Art, it seems, always teaches us something about the nature of desire.

The sometimes-overlapping periods of his work can be followed on his website. The early geometric work was said, by art historian Henry Adams, to “employ abstraction as means of direct emotional expression.” Such work soon encountered Raimondi’s growing interest in the environment, in mythic and historic figures, in jazz, and in Native America.

Hence, Raimondi spent months on Nantucket Island gaining insight into endangered species and the human impact on our fragile eco-systems. Insights that helped his vision for his work evolve into a more profound embrace of human freedom and purpose, an embrace that called for an allusion to both myth and history, to encompass both his emotional and aesthetic aims.

It is impossible to see, how all that would not have created for Raimondi, a connection to jazz and its improvisational nature, which is just where he was led. He tells the story of drawing and listening to Sarah Vaughan and ruining the ink of the drawing by the tears that her voice and words stirred in him. His jazz series is dedicated to many of the major legends in the world of jazz, those who created our authentically American art form and its offspring.

By this time fully launched into the mystical world, the world of spiritual depth, he also came to see that same profound world emerging from the experience of Native Americans and their leaders. Their wisdom emerges in his work in a new elegance of lines and shapes. Of course, here again, as in the improvisations of jazz or the conditions of natural life, he found his unique and powerful way of depicting fragility and fluidity with the size, solidity, and structure of bronze and steel, capturing the often still, small voice of fleeting moments in sculptures of enormous sizes.

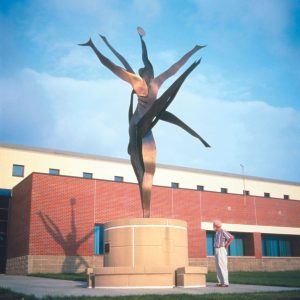

However, it was not the world-famous sculpture that Bill Nester had the vision to commission for UNK’s ATHLETA. Raimondi was still then much less well-known. The story of how he was chosen says something about John, about UNK, and about Bill Nester as well.

Raimondi’s competitors for that commission all submitted completed sketches of the sculpture they would see built. John, on the other hand, submitted an idea, the idea that he would not attempt such a sculpture without knowing more about the subject of the sculpture, the place and the people. That idea intrigued Nester, possibly because Nester and the others working with him were also champions of learning, which was just what Raimondi had proposed doing. Or perhaps Bill’s vast knowledge of jazz gave him a bit of insight into the character of the sculptor himself.

As it turned out, John came and spent a semester at then KSC, ensconced in the industrial arts wing of the old, now demolished Otto Olson, or out and about taking the hundreds of photos of athletes in motion that would ultimately inform the shapes and lines of the sculpture. Fortunately for what was once Kearney State College and is now the Kearney Campus of the University of Nebraska, the sculpture that once faced only a parking lot, now finds itself on a busy pedestrian thoroughfare between the Colleges of Business and Education on the west and the rest of the campus to the east.

When Raimondi was a major visitor to Kearney’s art scene, he accepted invitations to meet with classes, visiting Chuck Peek’s freshman composition class four times to speak to four different aspects of his work, the economics of his art, the industrial fabrication of the statue itself, the aesthetics of sculpture, and the story the sculpture would embody. For each aspect the students wrote papers, and John got to see the best of the lot.

Raimondi was often hosted by then Kearney residents Dave and Linda Raymond and by photographer Greta Sandburg and her late husband, psychiatrist Brick Murray. He made authentic Italian pizza for them, which even Dave, who then owned a pizza parlor, pronounced exquisite.

Working in cor-ten steel, aluminum, bronze and stainless steel, John since produced over one hundred works, each preceded by its formative sketches, and in most of which he was hands-on in the fabrication of the final monument. Like “gold to airy thinness beat,” his artistry turns solids into fluid and graceful form.

By Chuck Peek, with material from the Raimondi website and conversations with the artist.

John Raimondi website, sculpture Athleta